Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art

Record numbers through the door on the first day of 'Marvel: Creating the Cinematic Universe'. #MarvelGOMA

My argument, however, is that this kind of superficial blockbuster show, although popular, is not relevant to our society. What is needed is a more socially responsible approach in the provision of exhibitions and programs tailored to the complex and challenged social context of today.

Exhibitions like 'Marvel' are distractions 'against self-reflection and appropriate action’ (Janes, 2009, p. 27) in a world facing multiple crises across the globe. Sadly, in these times plagued with fears and instability, we are bombarded with imagery and scenarios that entice us into illusory worlds, in this case, the world of the superhero - where they have the power to overcome evil and divert disaster - giving us a false sense of security and deflecting our minds away from real critical concerns. We are brainwashed by marketing and the media and become blind to what’s really going on around us. And, though I haven’t seen any of the Marvel films, as a movie franchise, there is no doubt a plethora of related products are available for purchase by the audience. Robert Janes (2009) suggests that museums, ‘unwittingly or not, are embracing the values of relentless consumption that underlie the planetary difficulties of today’. Big international shows each seem to try to outdo the last in terms of scale and spectacle, such as ‘Gladiators’ at the Queensland Museum and superstar retrospectives of artists such as Cindy Sherman and David Lynch at QAGOMA.

The problem is that we live in a society that is driven by money and high consumerist expectations. What we expect is expensive and unfortunately, in these times of economic crisis, government funding to public museums is reduced and the expense of creating these kinds of shows to a demanding public, leads to anxiety about balancing the books. These spectacle shows - sometimes with quite hefty admission fees - lure the public in, where they are given ample opportunity to spend, thus helping to fill the museum coffers.

Janes describes a museum that focuses on consumerism as a ‘museum as mall’, a space that increasingly looks like a shopping mall, and offers various opportunities for the visitor to spend their money on dining, entertainment or products, while, per chance, having the opportunity to look at some art or objects from the collection. Children are often the focus of such entertainment strategies and merchandising has become such a huge component of the entertainment experience, that it is hard for museums not to join the spectacle-bandwagon and attract some of the spin-off spending in their direction. As suggested by Janes, ‘our unique challenge is the rise of marketplace ideology and museum corporatism, whose uncritical acceptance by museum practitioners has created a Frankensteinian phenomenon’(ibid, p. 24) .

Relevance, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, means to have bearing on or be connected to a matter in hand, to be closely related to a subject or point of view, or to be pertinent to a specific thing. The etymology of the word ‘relevant’ comes from the Latin root meaning ‘to raise up’, ‘relieve’, ‘help’, and ‘offer assistance’. Essentially, for a museum to be relevant, it needs to provide information that relates to and is helpful to the audience or community to which it serves.

Janes suggests that for a museum to be relevant it needs to be part of the discussion regarding critical global concerns such as climate change, environmental degradation, the depletion of fossil fuels and numerous local issues concerning the well being of our communities. He states that ‘various social, economic and environmental issues have now transformed into a critical mass that can no longer be ignored by government, corporatists or citizens’ (Janes, 2009, p. 24) and ‘museums must assume responsibility for (their) behaviour as a matter of survival’ (ibid, p. 27). He suggests that museums, as social institutions, have a responsibility to actively address these issues in a mindful way, instead of being caught up in the ‘chaotic cascade of museum chatter' (2009) concerned with anxieties about surviving in the marketplace and that it is time for museums to examine their core assumptions. It is all well and good to provide mega-shows that attract big crowds, but there needs to be a continuous push to address real social concerns and community interests as well. Janes suggests that instead of charting success by marketplace measures such as visitor numbers, measure it by the ‘yardsticks of kindness, relevance, community cohesion and other more psychological markers of good health’ (Janes, 2009, p. xiv). An appropriate question a museum needs to ask would be, 'Is this a worthwhile exhibition for our audience'? not 'Is this going to pull the most people'? Fiona Cameron suggests that most people expect the museum to be more socially minded, ‘bringing important, challenging and controversial points of view into democratic, free thinking society’(Janes, 2009, p. 61). In doing so, they enable public participation beyond the 'passive cultural consumption’ of ‘hyper-capitalism’(ibid p. 21-22). Museums must stop their ‘navel gazing’ and make it their mission to get involved in social issues and ‘advance the common good’(ibid, p. 54).

Embracing new ideas and confronting important issues should not risk compromising a museum's respectability by taking overt political stances, but voicing opinion should not be avoided altogether. It is not acceptable that museums should maintain a position behind its ‘veneer of moral and intellectual neutrality, remaining immune from pressing challenges of our day’(ibid, p. 19). 'It can be dangerous to shy away from criticism, challenge and provocation, which should be part of their role' (Museums Association p. 14). An example of an oversight might be that the sponsor is controversially mining on indigenous land, for example, and to keep this information hidden can cause offence where the indigenous public discover a lack of transparency. Communities need to be consulted. It is important to remember that 'although museum displays have the potential to create empathy and understanding, they equally can create ‘antipathy and misunderstanding, in a pluralist society’(Wehner and Sear, 2010). Where it is not evident what an audience wants, collaboration with the public creates a participatory museum, where the audience let the museum know what they want (Clifford, 1997).

Hooper-Greenhill suggests that 'post-museums' (sites for exposition of society’s basic values), embrace cultural heritage, social perspectives and values, the emotions of visitors and the concerns and ambitions of communities (ibid, p. 168). Museums can gain a reputation that upholds ethical and moral standards, while challenging critical social, economic, and environmental problems, difficult interrelationships regarding traditions and beliefs that abound in our multicultural society, and out-dated museum missions.

In the post-colonial era, museums have had to reinvent themselves as society changes, due to various social pressures. This has included enlivening their displays and collection to prevent becoming 'mausoleums' filled with dead things, when interest in them began to wane in the 1950s. But they have also become more democratic and inclusive, validating the wider global audience and their diverse experiences. Steven Conn states that 'the quickening pace of cultural levelling as a result of globalisation has increased specificity' (2010, p. 42) and James Clifford (1997) suggests that in an increasingly fragmented world, the assertion of difference has become more important, particularly in this time of heightened border control and refugee politics. Various audience groups should be consulted to ensure there is no omission or misinterpretation of information that might offend a group, but instead gives everyone a chance to be represented and express their perspectives and concerns. Museologist, Duncan Cameron, suggests that in these challenging times, museums have a responsibility to create democratic ‘forums’ for ‘confrontation, experimentation and debate…to ensure that the new and challenging perceptions of reality …can be seen and heard by all’(Janes, 2009, p. 30-1).

As well as recognising ethnographic and cultural difference, it has been important for museums to validate those who have traditionally been marginalised, such as indigenous people, women and disabled people. In providing them with a sense of belonging and identity, as well as the opportunity to have a voice about their interests and concerns, museums are made more relevant. Museums have realised that for museums ‘to matter more, they need to know what matters’ (Simon, 2015) to a diverse audience. They also need to create connections between their objects and displays and their audience's memories or experiences, while recognising that effectiveness of an exhibition wanes when people cannot relate personally to the information or objects displayed.

It may require challenging conventional practices and attitudes, as well as formalising mission statements to make clear the central focus on community issues and values. Janes suggests that learning is essential for the creation of innovative museums and it 'requires that we ask uncomfortable questions of ourselves and others' (Janes, 2009, p. 17) , as well as an 'expanded consciousness, reflection on habitual performance and consideration of options’ (ibid, p. 19). Museum workers need to employ insight and innovation to address new and critical social challenges, as well as consider new ways of attaining socially-appropriate funding.

Given that they are often reliant on fulfilling the requirements of corporate funders, there is anxiety to prevent potential to overstep the corporate requirements of partnerships. In the case of the Marvel show the main sponsor is Deloitte, a finance firm who would, of course, place money at the top of their priority list. Perhaps for museums to have greater social connectedness with their communities they need to make greater effort to attain sponsorship from those who care most about confronting real community issues and engaging the public in important community matters. For example, as suggested by Janes, heritage foundations, community organisations, humanitarian organisations, health care providers and private philanthropists may be lobbied for funding for exhibitions and programs. These funding bodies may also be more interested in approaching museums that have a reputation for bringing socially responsible exhibitions to the attention of the public, but this is unlikely, where a museum employs ethically questionable and ‘self-congratulatory rhetoric’ in grandiose themes, branding and marketing, ‘where hype and hyperbole are requirements of the business model’. (ibid , p. 39) Investors may also be interested to provide ‘risk capital’ (ibid) that enables a museum to develop new ideas that challenge tradition and bring relevant, valuable and meaningful possibilities to fruition.

Janes’ mindfulness model of museums means having moment to moment awareness…'paying attention to things we ordinarily ignore’ (ibid, p. 147). By this he means that museums need to stop focusing on internal organisational distractions and marketplace economics. He states that 'failing to ask why museums do what they do limits awareness, organisational alignment and social relevance’(ibid, p. 14). He suggests doing this by employing ‘orthoganal thinking - thinking at right angles to convention' - to create dialogue and debate that may lead to solutions to social problems. He considers an ideal museum as a ‘locally embedded problem-solver in tune with the challenges and aspirations of the community’ (ibid, p. 173).

With respect to problem-solving, a central concern for museums has been to adapt their indigenous representations from stereotypes of primitivism and exoticism, to displays that empower rather than degrade indigenous people. Historically, colonialism has inflicted terrible wounds onto indigenous society, through murder, destruction of their cultures and attempts to convert them to our ways of living. Many of their languages and cultural heritage practices are being forgotten and they continue to fight for equal and basic human rights. The International Forum of Globalisation state that indigenous people have had no voice and have been ‘easily swept aside by the invisible hand of the market and its proponents. Globalisation is not merely a question of marginalisation of indigenous people; it is a multi-pronged attack on the very foundation of their existence and livelihoods’ (Janes, 2009, p. 50). It is worth noting that there is no significant display of our First People at the Queensland Museum, another glaring concern.

There has been an improvement in the attitude toward indigenous people in recent years, with museums as 'transcultural artefacts', (Wehner and Sear, 2010) creating ‘contact zones’ (Clifford, 1997), allowing indigenous people the right to share authority over the meanings produced in museums regarding their objects, and the opportunity to share their knowledge to help create displays that can have relevance to both indigenous and non-indigenous people, reminding us of the violence of the past, while creating more equity in validating their position, values and beliefs. The museum can, in this way, ‘stewarding the ethno-sphere’ (Janes, p. 50), that is, help to ease the frictions between indigenous and non-indigenous people, and help pave the way to future relationships that are more tolerant, constructive and mutually respectful.

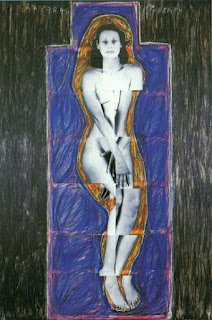

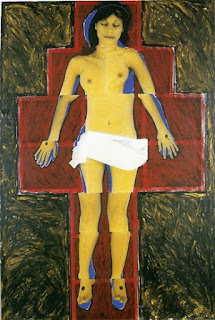

As well as engaging with their community, museums can work in collaboration with other museums or organisations, locally, regionally and internationally, ‘synthesising…an understanding of the interconnectedness of the problems we face...environmental and social;…empowering and honouring all people in search for a sustainable and just world’ (ibid, p. 166) . ‘Skin' was a good example of a worthy partnership between the National Portrait Gallery and Canberra Youth Theatre (CYT). It was a response by the CYT to the exhibition 'Bare: degrees of undress' and was a devised performance installation as part of the exhibition, which allowed the CYT to reach a broader audience and improve awareness of their youth service. People, specifically, young people were centred upon in the examination of literal and metaphorical exposure and vulnerability. Problems faced by youth were tackled within the broader subject of portraiture.

Skin

At the Imperial War Museum in London, there have been a number of exhibitions that reflect on human rights issues, including ‘Crimes Against Humanity: An Exploration of Genocide and Ethnic Violence’ (ibid, p. 50). Also, a more recent show 'People Power: Fighting for Peace' draws on testimonies from their collection, in an exploration of wide-ranging reasons for opposing war as well as the nature of conflict and its evolution from trench warfare to nuclear weapons. It coincides with a conference entitled 'Protest, Power and Change', organised by the Movement for the Abolition of War in collaboration with the museum. Also, the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, 'is the only global network of historic sites, museums and memory initiatives that connect past struggles to today’s movements for human rights. We turn memory into action'. They are dedicated to remembering struggles for justice, focusing on issues such as genocide, child soldiers and sweat shops, with the aim of providing programs and exhibitions that stimulate dialogue about injustice, promote humanitarianism and democracy and providing opportunity for the public to engage in the discussions (ibid). For example, 'Body mapping in Uganda' is an exhibition of 'body-maps', created by survivors of the civil war in Sudan to tell their story and come to terms with past conflict and atrocities, capture the trauma of their experiences and engage with the past while envisioning a new future.

The Independent Scholars Handbook suggests the use of ‘intellectual activism’: tools which do not necessarily create new knowledge but make existing knowledge more accessible, understandable and useful to others’ (ibid, p. 23). A museum can tap into its collections and find ways to connect people to the objects of the past for the knowledge made visible through them. Also, internal and external staff and consultant knowledge should be sourced to provide vision and creativity in achieving museum goals. For example, there is a collaborative research centre at the Australian Museum, that considers environmental concerns. The Australian Museum Research Institute brings together a team of scientists, collection officers and students. They focus on some of today’s major challenges: climate change impacts on biodiversity; the detection and biology of pest species and understanding what constitutes and influences effective biodiversity conservation. The natural history collections of 18 million objects, underpins their research and one of their main assets is the use of wildlife genomics to solve key problems. They communicate their research widely, inspiring interest in the natural world and informing decision-makers, thus making important contributions to society and the environment and provided scientific answers to thousands of queries from government, media and the general public.

The Buffon Declaration also address environmental challenges, and represents 93 museums of natural history, gardens, zoos and research centres, from 36 countries. Each museum offers vital contributions in their repositories of specimens, in their research, in their partnerships and programs. They call on governments to change the focus from profit-oriented bioprospecting' to 'science-oriented research for the public good' (Cameron and Neilsen, 2015 p. 37) They provide forums for the public to directly engage with current information and assist policy makers to reform behaviours to assist in the restoration of ecosystems under threat. Their 'sentiment translates into action' (ibid, p. 44).

Museums can share resources and collections and take their objects to the people in outreach programs, which is particularly important in regional areas that often get forgotten. Access to the collection and information is important for the local and global community, with the internet visitor being an important consideration. Virtual access to objects in a 'digitally distributed museum' (Harris and O'Hanlon, 2013) opens up the collection to a virtually limitless audience, although internet access is not yet equitable. Such access can create interest in the museum and entice actual visitation for an authentic engagement with the collection and the community.

The Australia Council offers a range of government grants to art museums, while funding for touring exhibitions is available through Visions of Australia and the National Collecting Institutions Touring and Outreach Program which fund the development and touring of exhibitions of cultural material of historic, scientific, design, social or artistic significance, and regional and remote venues are a higher priority for funding. Metropolitan museums also need to assist regional areas to be recognised as contributory places, rather than distant and unimportant. Larger, travelling exhibitions from metropolitan areas give regional communities opportunities to see work that is of national or global significance without having to go to the city. Regional museums contain amongst their treasures many works of national as well as local significance which should be utilised for public engagement, to remind the community of their importance in the local and national interest. A local focus gives those communities a voice, recognition and pride.

Educational tourism is an area of importance also, as museums are relevant for teaching purposes, and with the NBN there will be greater collaboration between museums and teachers and their school curriculums in the future (In the national interest). Other access issues include accommodating the audience in the provision of reasonable entry fees (and only where necessary), and allowing adequate opening hours (Simon) or enabling a loan to source communities of their objects for ritual purposes.

Museums need to create new ideas and stimulate creativity in all areas of thinking and activity in order for them to remain relevant to the public. Janes suggests that a disabling condition of museums in achieving social relevance is ‘the tyranny of tradition’, where museums create inertia with tired, uncritical methods and practices. However, museums can be reenergised with undertakings and collective missions that are ‘imbued with wisdom, courage and vision’ (Janes, 2009, p. 14). Homer-Dixon suggests that ‘institutions need to ‘overcome the illusion that besets the world’ (ibid, p. 52) in an attempt to create solutions to problems that threaten our survival as well as the survival of museums. What we don’t need are blockbusters continuums that avoid tackling challenging issues that we face as a local and global community. At some point, along with the ‘growing disillusion with buying stuff’(ibid, p. 53), people may just as easily become disillusioned with museums and their attempt to draw us in and empty our pockets. What we may instead be pleasantly surprised in, are the ‘indivisible benefits’ of the common good, that is, justice, peace, clean air (and) clean water (ibid, p. 53). Ursula Franklin, humanist and physicist, states that we give up our autonomy and pay taxes in the hope that government will protect 'indivisible benefits’ (ibid, p. 54). However, this safeguarding has deteriorated in the name of economic growth. 'Erosion of stewardship' (ibid) due to the belief that continuous economic growth is essential to a health society needs to be controlled for the benefit of society at large. Museum performance such as attendance figures, earned revenue and shop sales are now the primary measures of worth for most museums, with gvernments, corporations and private funders clearly demonstrate, time and again,' their inability to separate common good from private gain’ (ibid p. 53). And private gain has no relevance to the community at large. What is relevant is finding a way to deal with our global differences and similarities so that we might gain a more unified, less antagonised global society, one that recognises and respects unique qualities of others, appreciates the reflective collections of our pasts, teaches rather than tempts our children, collaborates together to find reasonable solutions rather than blindly avoiding critical concerns that, locally or globally, may affect us all.

References

Alberti, S. J. M. M. (2005) ‘Objects and the Museum’, Isis, 96(4), pp. 559–571. doi: 10.1086/498593.

Alberti, S. J. M. M. (2009) Nature and culture: objects, disciplines, and the Manchester Museum. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Australian Museum Research Institute [website]. Available at https://australianmuseum.net.au/amri.

Bennett, T. and Ebooks Corporation (1995) The birth of the museum: history, theory, politics. London: Routledge. Available at: http://www.UQL.eblib.com.AU/EBLWeb/patron/?target=patron&extendedid=P_1487028.

Cameron, F. and Neilsen, B. (2015) Climate change and museum futures. New York, Routledge.

Carmichael, E. (2016, April 27) How libraries and museums can stay relevant – Madrid 2016 full presentation [video file]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOyW4wIqk_4.

Clifford, J. (1997) Routes: travel and translation in the late twentieth century. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Conn, S. (2010) Do museums still need objects? Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Dudley, S.H. (2010) Museum materialities: objects, engagements, interpretations. New York, Routledge.

Englund, V. (2017) Marvel: creating the cinematic universe GOMA, Must do Brisbane. Available at http://www.mustdobrisbane.com/kids-whats-on-kids-whats-on/marvel-creating-cinematic-universe-goma.

Fromm, A. (2016) Ethnographic museums and intangible cultural heritage return to our roots, Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 5, p. 89-94.

Harris, C. and O’Hanlon, M. (2013) ‘The future of the enthnographic museum’, Anthropology Today. United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 29 (1), pp. 8–12. doi: 10.1111/1467-8322.12003.

In the national interest: the National Museum of Australia (2011) Sydney, N.S.W.: ABC1 [video file]. Available at: http://www.library.uq.edu.au/mget.php?id=UQL_ARMU2014_Video28.

Janes, R. R. (2009) Museums in a troubled world: renewal, irrelevance or collapse? London: Routledge. Available at: http://ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/login?url=http://www.UQL.eblib.com.au/EBLWeb/patron?target=patron&extendedid=P_431812_0&userid=^u

Macdonald, S. (2006) A companion to museum studies. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Pub. Available at: http://ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/login?url=http://www.UQL.eblib.com.au/EBLWeb/patron?target=patron&extendedid=P_284278_0&userid=^u

Museums and galleries national awards (2017) Museums Australia. Available at https://www.museumsaustralia.org.au/museums-galleries-national-awards.

Museums Association (2005) Collections for the future: Report of a Museums Association Inquiry. Available at: http://www.museumsassociation.org/download?id=11121

Neilsen, J.K. (2015) The relevant museum: defining relevance in museological practices, Museum management and curatorship, vol.30, issue 5. Available at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09647775.2015.1043330?journalCode=rmmc20.

Simon, N. (2015, July 28) Meditations on relevance, part 1: overview. Museums 2.0 [blog]. Available at http://museumtwo.blogspot.com.au/2015/07/meditations-on-relevance-part-1-overview.html.

Simon, N. (2010) The participatory museum. Santa Cruz, Calif: Museum 2.0. Available at http://museumtwo.blogspot.com.au/2015/07/meditations-on-relevance-part-1-overview.html.

Stanford Alumni (2013, May 6) Wanda Corn, 'the future of museums' [video file]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LiSPoVG3NV8.

The Agenda with Steve Paikin (2012, Feb 21) Do museums still matter? [video file]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-91GqSBnUUs.

The Aspen Institute (2013, August 8) Do art museums matter anymore? Full session [video file]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HWKfUEdwYsI.

Wehner, K. & Sear, M. (2010) 'Engaging the material world: object knowledge and Australian Journeys', Museum materialities: Objects, engagements, interpretations, p. 143-161.

Wilkinson, Helen. (2005) Collections for the Future: report of a Museums Association inquiry, Museums Association.

Woodham, A. (2014, March 6) The concept of relevance for museums and heritage sites. Available at www.dissertationreviews.org.