Women's art can be classified in terms of two dominant paradigms: firstly, a focus on representing women and their experience by foregrounding their subjectivity, knowledge and/or concerns in forms negated or omitted by masculine iconographic traditions; secondly, a focus on critiquing or deconstructing the prevailing masculine representations of women and of the world in general.

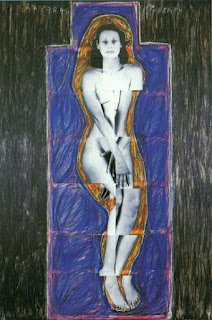

I have chosen to discuss the way in which Julie (Brown) Rrap's work 'Puberty' and the 1984 installation 'Persona and Shadow' from which it is a part, critiques and deconstructs the prevailing masculine representation of women, while offering feminine subjectivity to the objective experience.

| |||||

| Rrap 'Puberty'1984 |

| ||

| Munch 'Puberty' 1894 |

Julie Rrap's investigation focuses on the representation of women in the misogynous tradition of art history. For example, the original Edvard Munch painting 'Puberty' painted in 1894, shows an adolescent girl sitting self-consciously on the side of a bed, naked and vulnerable, posed passively for the intended male viewer, her expression blankly directed at the viewer, while her dark shadow looms on the wall behind her. She not only symbolizes purity, but also the impending loss of innocence. Bram Dijkstra says that in 'seeing purity, the late 19th century mind was titillated - or disturbed - by thoughts of sin...the disturbing unfolding of women's essence' (Dijkstra1986:178). Filled with signs of threat, this image represents rape, 'a promise of unopposed carnal knowledge offered to the viewer' (Dijkstra 1986:191).

The theme of the work is typical of the era in which it was produced, exhibiting hatred, dislike, mistrust, or mistreatment of women. The sole purpose of women at the time was to be sexual and reproductive and they were seen as a temptation that threatened the spiritual advancement of male intellectuals and thus, to be feared. In order to retain power, feminine archetypes were created by men, including Virgin, Mother and Whore, where women were eroticized and victimized, represented as pure, passive and submissive objects of male desire.

The historical representations of women has deeply affected our preconceptions of what it is to be female. It is this legacy of voyeurism and feminine personas that Rrap intends to debunk. In an attempt to insert herself into the overtly masculine art tradition from which women as artists have been virtually excluded throughout history, Rrap uses the relatively recent medium of photography, as its images are inherently objective and it is a medium not dominated by males to the extent of the other art mediums, to attack masculine power within art historical discourse.

It is a common feminist strategy to subjectify their experience in performance and photography, while opposing the stereotypical female roles that humiliate women. Rrap refers to the roles she plays in these images as 'speaking as the male speaks, evading as the male evades, play acting life as men play act it' (George Paton Gallery 1984) and makes an attempt to liberate women from these inferior roles and gain worth and social equality. By replicating the original image to the degree that it is recognizable as a copy of the original image and by adding her own elements to the image, such as incorporating the date '1984', using photo-montage, removing the imposing shadow and the image of the bed, she thus subverts the stereotype and exposes the fraudulent, constructed nature of feminine desire and sexuality.

Rrap's aesthetics are pleasing and her image is as much an image of desire as the original. It is a large, glossy, color cibachrome print, seductive and fetishistic, thus claiming an audience but also asserting irony and wit.

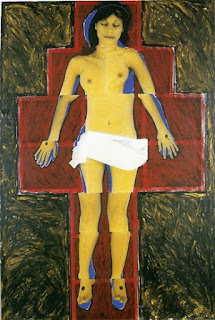

The 'Persona and Shadow' images are not self-portraits, but rather, masquerades that allow the artist an active role in her depiction, rather than remaining a passive model for a masculine perpetrator. She plays iconic roles including Christ and Madonna, a sister, a siren, a senex (a wise old man archetype), a virago ('a term referring to a woman who is manly in character but not necessarily appearance...who steps out of the domestic role and sometimes oversteps her boundaries as a woman. She never takes shit from a man and always holds her own. She keeps a man from walking all over her and she never, EVER, downplays her importance in order to charm a man' (http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Virago).

|

| Christ |

|

| Madonna |

|

| Virago |

|

| Sister |

|

| Pieta |

|

| Siren |

|

| Senex |

|

| Conception |

By using herself as the model, Rrap challenges the objectification and sexualization of the female body. She maintains control over her image and her body, she directs her gaze to herself behind the camera and to the audience and in doing so, blurs the distinction between active and passive, repressed and liberated, artist and model. Rrap's body represents the history of the female body in art, a 'body with its full weight of culture' (George Paton Gallery: 1984).

Although she mimics the historical representation, she re-articulates the body through various techniques of de-naturalization and fragmentation, incorporating her own ideas and marks into the original images. Through manipulation of the print with colorful marks, using multiple photographs to represent the body, Rrap highlights the fact that the female body is a site of textual production, a 'spectacle of feminine fabrication' (Moore 1994:99) and calls into question the assumed naturalism of artistic codes, deliberately highlighting the artifices of historically constructed feminine identities. In minimizing the depiction of the female form to a two dimensional space, with the removal of the signifiers of bed and shadow, our attention is drawn to the representation of the body itself, a body free from the threat of impending assault. It brings our attention to the fact that art history has constructed its representation of women. The problem that I have, however, with the representation of the female body as nude, is problematic, as it invites voyeurism, it offers no boundaries or protection from intruding gazes. The only way it really works is that the gaze back to the audience is a strong one, defiant. Do we see male nudes in the same way as female nudes? Is there a proliferation of male nudes in representations? There are classic sculptures, such as the statue of David, that celebrate the male nude, but they are positively strong representations, with a hint of modesty. I'm not sure that female nudity is really such a strong statement for the cause of equality in representation of the human form. Perhaps we should be taking our body back out of the gaze, keeping it private and not encouraging any rights to openly view our bodies. Or, is it helpful to have healthy representations of female nudes to reduce the potential to sexualize them? How would it seem if it were men in this situation? Would they be shown to be vulnerable or strong?

Beneath or surrounding her body in these images are borders. Is she a displaced individual still within the confines of tradition or has she risen above the uniformity and conformity of the past? Its hard to say without reference to the artist's statement: ‘with the Munch images, my own figure is fragmented and displaced, squeezed into an apparently immutable outline inherited from history. It was about the discomfort of imagery that we can’t alter now. How do you deal with it – these representations of your own sex, where women are so confined and limited?’ (MCA: see link). I'm not sure that the suggestion is strongly defiant, however, it is an active attempt to deconstruct the initial stereotypical guises and so certainly takes the reins in enabling attitudinal change.

In marking the photograph, Rrap adds meaning. She states, "One of my earliest influences in this regard was the work of the Austrian artist Arnulf Rainer, whose self-portrait work 'Face–farce' was recorded photographically by an assistant while the artist was under the influence of the drug mescalin, rendering him psychologically 'absent’ from the process. In revisiting these images of himself, Rainer attempted to use this photographic ‘proof’ as a trigger to recreate his memory of the event by drawing and painting on the surface of the image. This gesture exposed the disjunction between the ‘objective’ eye of the camera and the ‘subjective’ interpretation of the artist/viewer. His mark-making on the surface of the image was an attempt to expressively reach across this void between image, sensation and memory" (MCA: see link below). So too, Rrap attempts to add some personal expression to what could otherwise be seen as a simple objectification of her body.

Rainer 'Face-Farce'

Links

MCA - Julie Rrap education kit

https://www.mca.com.au/media/uploads/files/2007_Julie_Rrap_Education_Kit.pdf

Julie Rrap website

http://www.julierrap.com/

Bibliography

Brown-Rrap, J (1988) Julie Brown-Rrap, Grenoble: Ecole des Beaux Arts

Dijkstra, B (1986) Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siecle Culture, New York: Oxford University Press

George Paton Gallery (1984) Julie Brown: Persona and Shadow, Parkville, Victoria: George Paton Gallery

Heller, R (1984) Munch: His Life and Work, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Kirby, S (1992) Sight Lines: Women's Art and Feminist Perspectives in Australia, Toronto, British Virgin Islands: Craftsman House/Gordon and Breach

Moore, C (1994) Indecent Exposures: Twenty Years of Australian Feminist Photography, North Sydney: Allen and Unwin/Power Institute of Fine Arts.

No comments:

Post a Comment